The Ties That Fray: Memory, Meaning, and the Union’s Uneasy Future

There’s a growing assumption—comforting to some, convenient to others—that history is drifting inexorably toward Irish unification. The logic runs that Northern Ireland is economically burdensome, politically unstable, demographically changed and culturally alien to modern Britain. Best, then, to quietly let it go.

In this, Republicans find their narrative confirmed. But so too, increasingly, does a British political class that sees Northern Ireland not as part of the Union, but as a problem ‘over there’. Something to be “managed,” not understood.

Yet history, as ever, resists neatness. The Union is not a romantic fiction, nor a colonial relic waiting to be discarded. It is, and has long been, a hard-won compromise. One born not of sentiment, but necessity: England weary of Jacobite threats and cross-border unrest; Scotland economically bruised by the Darien disaster; Ireland the long and bloody outlier; Wales already subdued by conquest. One could easily – if simplistically – conclude that this was not some grand design, but a kind of constitutional damage-limitation exercise. And that it worked—unexpectedly well.

Out of this grew a force that helped shape the modern world: military, industrial, cultural. The Royal Navy and Scottish regiments. Belfast shipyards and Lancashire mills. Empire, for better or worse, made in common cause. But the terms of that union were always uneasy—and now, increasingly, unremembered.

My own family sits in the middle of this tangle. My grandmother, from Armagh, was a Catholic. Proudly Irish. She used to say she once danced with Michael Collins—though she had little time for ‘the boyos’, as she called them, or the men of violence. Her brothers fought for Britain in the First World War, and one, she claimed, rescued a wounded officer from no man’s land on the Somme and was recommended for the Victoria Cross. But the recommendation, she would add with a bitter shrug, was never made. Too Irish. Too drunk. Too much trouble.

One story had him striking a sergeant while in his cups, then lashed to a wheel in field punishment—until passing Australians, moved by colonial kinship or merely mischief, cut him loose. Apocryphal? Probably. Stirred from several grains of truth and, with many other ingredients added, whirled into a story too good to contradict.

The records show he was wounded at Loos and invalided out before the Somme began. But the facts hardly matter. They rarely do in families. What lived on was the mix of grievance and grace, pride and betrayal. She also recalled – among a mist of memories – Queen Alexandra, visiting a hospital, pausing to stroke the blonde tuft of hair on the bandaged head of one of her brothers. The monarch’s tenderness and the War Office’s indifference existed in the same story, the same breath.

As it turned out, soldiers were her thing. And so she married one.

That kind of complex, lived identity is increasingly rare—and politically inconvenient. Today’s narratives prefer clarity: Scotland is chafing, Wales’ dragon is awake in the hills, Northern Ireland is drifting, England is resentful. And through this lens, the Union looks like an inheritance we neither understand nor much want.

But to dismiss it is to forget too much. Belfast, like London and Coventry, was bombed in the Blitz. Short Brothers relocated there from the Medway to manufacture the Sunderland flying boat, a critical tool in the Battle of the Atlantic. The north and west coasts of these islands remain – as Leo McKinstry reminds us in Cinderella Boys, his history of Coastal Command – our first line of defence. A fact we forget at our peril.

The managerial class, with its instinct to cut losses and simplify narratives, finds the Union cumbersome. But history is never clean. It is full of ambivalence. The Union may be a compromise—but it is a living one. And in that compromise lies strength.

If we are to lose it, let us at least be honest about why. Not because history insists. Not because some deeper truth has revealed itself. But because, after years of fatigue and forgetfulness, we simply chose to stop making the case.

That is not destiny. That is abdication.

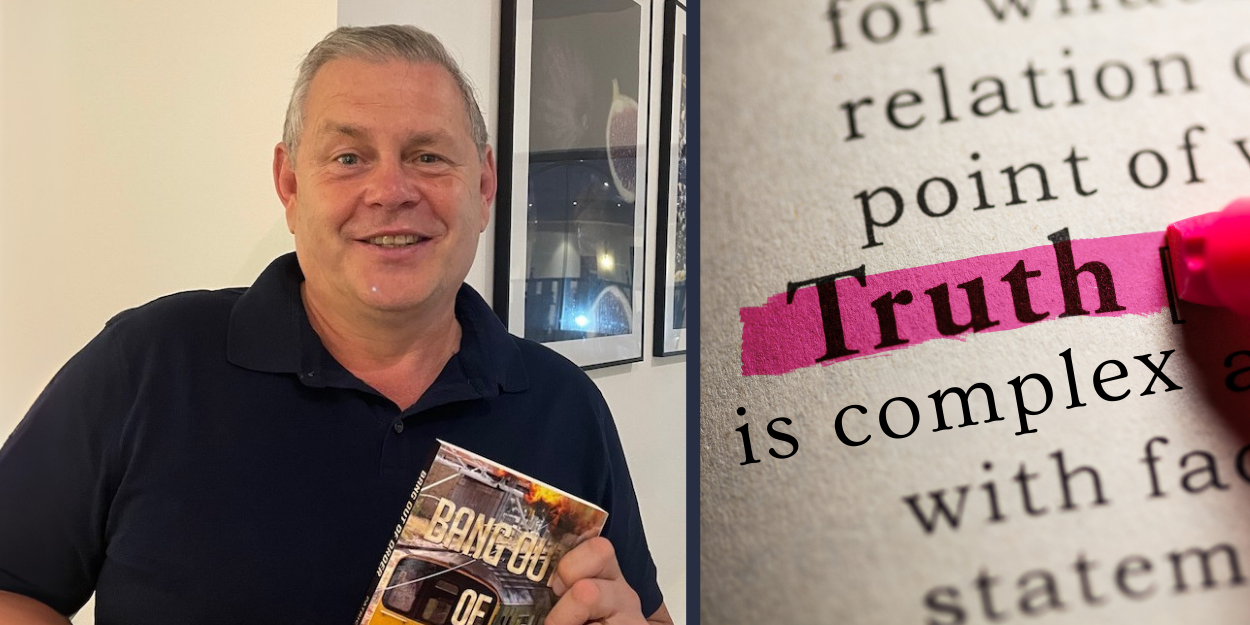

Patrick Barrow, author of the novel Bang Out of Order, a 1970’s detective thriller about The IRA, a South London Train Station explosion and an orphan’s son searching for his mother.