VE Day 80: Understanding the Importance of Northern Ireland’s Contribution to UK Defence in 1945 and What This Means for Our Defence Today

In marking the eightieth anniversary of VE Day, it is important to recognise the special contribution made by Northern Ireland to UK national defence in the Second World War and, crucially, its public policy implications for us today.

Given the relatively small size of Northern Ireland, the scale of its contribution to the leadership of UK defence during the Second World War was extraordinary. Between May 1940 and the end of the conflict the overall leadership of the British military was in the hands of people who were either immediately from, or whose roots went back to, Ulster. Field Marshal Sir John Dill, born in Lurgan and educated in Belfast, was Chief of the Imperial General Staff from May 1940 until the end of 1941, when he was succeeded by Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, whose family came from Fermanagh, who served as CIGS until the end of the war. In addition, Ulster also contributed Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery, General Sir Claude Auchinleck and General Harold Alexander.

The territory of Northern Ireland, meanwhile, provided the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland with an enormous geostrategic asset in the Atlantic, guarding the western approaches that were of such critical importance for a country like the UK that imports so much of its food. Alluding to her role in keeping open the Atlantic transport routes, Churchill observed: ‘Ulster stood a faith sentinel’ and ‘But for the loyalty of Northern Ireland and its devotion to what has now become the cause of Thirty Governments or Nations we should have been confronted with slavery and death, and the light which now shines so strongly throughout the world would have been quenched.’

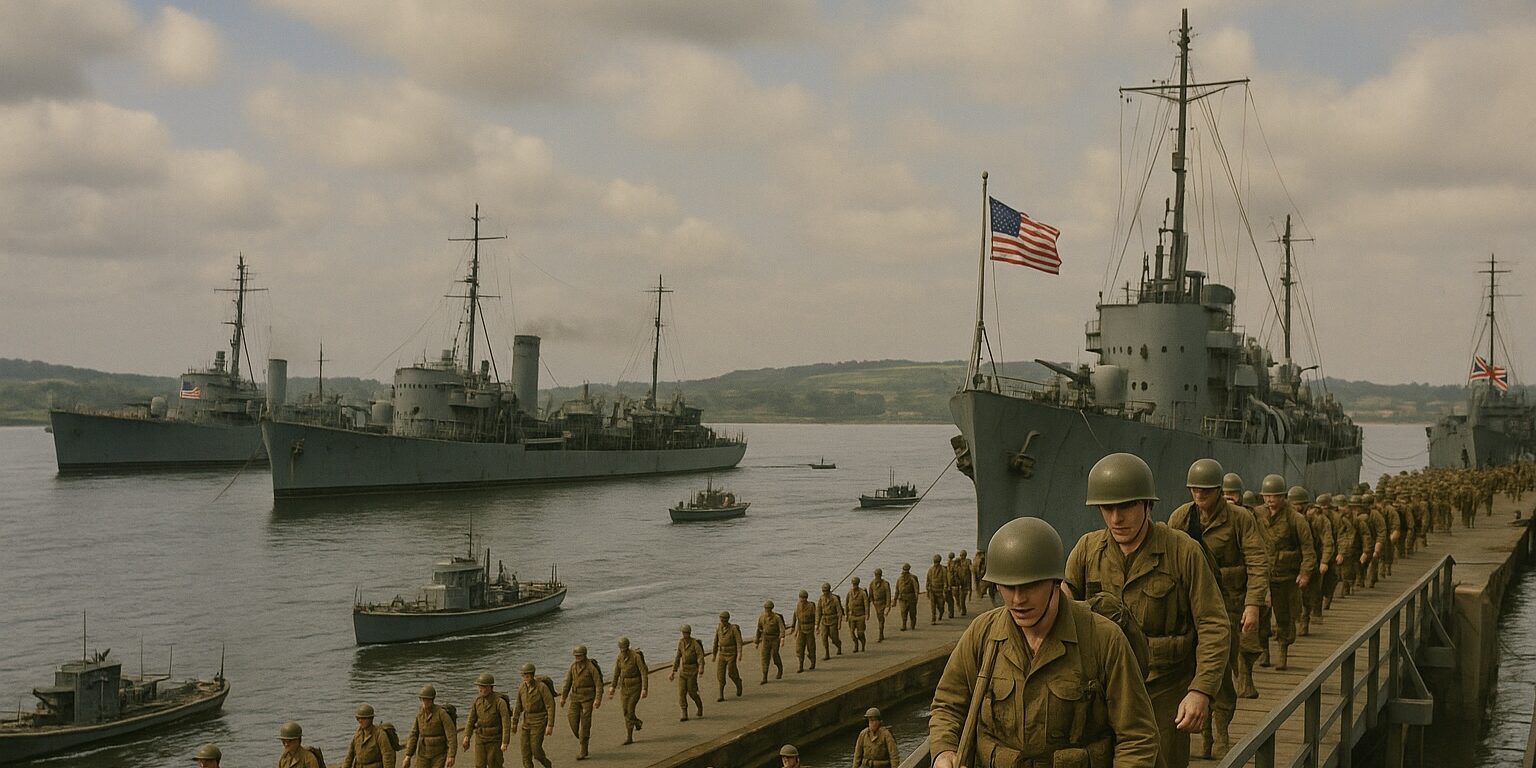

In addition to providing multiple UK RAF and RNAS bases, Northern Ireland, the first place in Europe to receive American troops, also provided the United States with airfields and its largest naval base in Europe at Foyle. It was here that the German U boat fleet finally surrendered in 1945. Over the course of the war a staggering 300,000 US military personnel were based in Northern Ireland which also saw the reformation of the elite US Rangers Unit, honoured by a dedicated museum in Carrickfergus today.

Northern Ireland was particularly involved in UK-US D-Day preparations. The Royal Ulster Rifles was the only UK regiment to send in two battalions on 6 June 1944. Speaking in Belfast in 1945 the future US President, General Eisenhower did not hold back when he said, ‘Without Northern Ireland I do not see how the American forces could have been concentrated to begin the invasion of Europe.’

After the war, on 5 January 1949, the Cabinet was advised by leading Whitehall Officials that:

‘…it has become a matter of first class strategic significance for this country, that the north should continue to form part of His Majesty’s dominions. So far as can be foreseen, it will never be to Great Britain’s advantage that Northern Ireland should form part of a territory outside His Majesty’s jurisdiction. Indeed, it seems unlikely that Great Britain would ever be able to agree to this, even if the people of Northern Ireland desired it.’ (Report by official working party of officials dated 1 January 1949 in PRO CAB 21/1842.)

Meanwhile, Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke’s nephew, and Northern Ireland PM Sir Basil Brooke stated: ‘A loyal Ulster within the United Kingdom is a bulwark of British security, as the experience of the last war strikingly proved. An Ulster incorporated in a non-British Ireland would be lost to Britain as a fighting force and a strategic base. Because of its important strategic position Northern Ireland must play a vital part in the scheme of defence, particularly in maintaining the security of the North Atlantic area.’

Of huge importance a similar observation was made by a seminal Policy Exchange report published in February 2024: Closing the Back Door Rediscovering Northern Ireland’s Role in British National Security. Having set out the current security challenges facing the UK, including the shift in Russia’s maritime doctrine in 2022 to prioritise the Arctic and Atlantic, the report concluded: ‘Northern Ireland is therefore the key to addressing the UK’s security concerns. Resurrecting the RAF and Royal Navy presence in Northern Ireland will bolster our forward presence for maritime patrol operations around our coastline, as well as into the GIUK Gap and beyond. In light of Russian aggression, recent government strategic documents have flagged our stretched naval and air capabilities in the north. Northern Ireland can therefore strengthen our strategic options in the region, whilst alleviating the burden on other bases, such as HMNB Clyde and RAF Lossiemouth.’

This new geopolitical context yet again calls into question the appropriateness of the Windsor Framework which divides the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland into two by means of an internal Sanitary Phyto-Sanitary (SPS) and customs border, making Great Britain legally a ‘third country’, i.e. a foreign country for some purposes, in relation to the whole island of Ireland. Implicit in this arrangement is the subjection of Northern Ireland to EU law in 300 areas but without representation. The current arrangements incentivise Northern Ireland to leave the UK in that, in the context of the Irish Sea border, the only prospect the people of Northern Ireland have of becoming full citizens again – able to stand for election to make all the laws to which we are subject – is if they seek a border poll and vote to leave the UK and join the Republic of Ireland, wherein their right to stand for election to make all the laws to which they are subject will be restored. In coming to terms with this dynamic, it is important to understand that while a particularly stark expression of the strategy, this is classic Europe integration and what academics working in the field call ‘functional spillover.’ The idea is that each step towards integration creates new tensions that can only be resolved by taking a further step of integration.

There are huge ethical questions about the appropriateness of any country allowing a portion of its population to be effectively encouraged to leave by means of partial disenfranchisement in their home country and the offer of full re-enfranchisement in another (in flagrant violation of the Good Friday Agreement democracy protections), when the people concerned have not already voted to leave. As I have argued elsewhere, by far the biggest questions arising from this pertain to the damage done to the ‘integrity’ the UK as a moral community that can believe in itself. It will be quite difficult to hold one’s head up and exhibit a sense of moral purpose in engaging with the wider world having treated a portion of one’s own people in this way. However, other questions also arise including whether – especially in the current geo-strategic context – it is in the interest of the wider UK (and indeed the US) to incentivise loss of control over the western approaches provided by Northern Ireland.

Note: This article was reproduced with Dr Boucher’s permission, having first been published in Parliament News.

Dr Dan Boucher, originally from Dorset, was Director of Policy for the DUP and stood as a TUV/Reform Candidate in the 2024 UK General Election